Dancing Dwarf Galaxies Could Hold Clues to the Milky Way’s Fate

Researchers at the University of Queensland have been tracking the motion of dwarf galaxies to determine whether the Milky Way’s future is typical compared to other regions of the cosmos.

Partnering with the Australian National University’s Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics and others, the team conducted the Delegate survey. Their findings suggest the Milky Way may be heading toward a dramatic celestial choreography — a merger with nearby dwarf and spiral galaxies.

“The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies, along with their smaller dwarf companions, are expected to merge in around 2.5 billion years,” said Dr. Sarah Sweet from UQ’s School of Mathematics and Physics. “Although there’s extensive research into our Local Group, we still don’t know how representative this scenario is.”

Satellite Galaxies in a Galactic Waltz

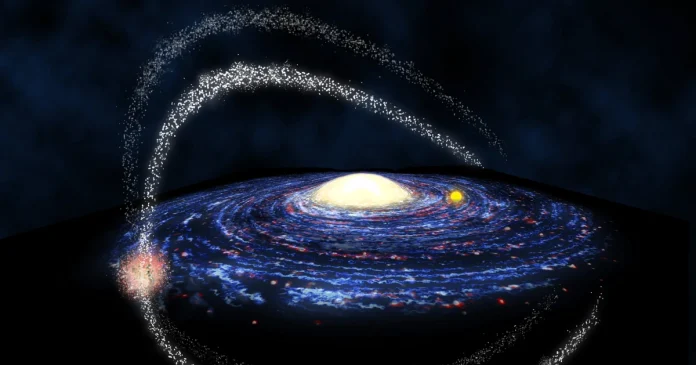

The researchers focused on two spiral galaxies, NGC5713 and NGC5719, that are about 3 billion years further along in their merger timeline compared to the Milky Way and Andromeda. These galaxies appear to be engaged in a gravitational dance, drawing in nearby dwarf galaxies that rotate around them in elegant patterns.

Without such mergers, dwarf galaxies might remain scattered randomly across space. But the observed systems show how these small satellites can form organized, disk-like planes — much like those found around the Milky Way and Andromeda.

Unlocking the Secrets of Galactic Formation

“This could be one of our best opportunities yet to understand how systems like the Milky Way’s satellites come together — and what might happen to them over time,” Dr. Sweet explained.

She added that by studying these dynamics, astronomers can sharpen models of galaxy formation, dark matter behavior, and the broader structure of the Universe. “It also gives us a humbling perspective on our place in a much larger story.”

Testing the Typicality of Our Local Group

As part of the Delegate survey, several upcoming papers will delve deeper into these findings. Lead researcher Professor Helmut Jerjen from ANU explained that the study is comparing the Milky Way and Andromeda to similar twin galaxy systems elsewhere in the Universe.

“We’re trying to find out whether our Local Group is the norm or an exception,” Jerjen said. “Until we can answer that, we’re limited in how much we can apply local galaxy data to the broader understanding of cosmic evolution.”

One lingering mystery is why dwarf galaxies are often found in flat, organized planes rather than scattered randomly — something not fully predicted by even the most advanced cosmological simulations.

Rewriting the Models of the Universe

The fresh data from the Delegate survey indicate that existing simulations of galaxy mergers and satellite behavior may need significant updates.

“Will the Milky Way start its own celestial dance with Andromeda, surrounded by swirling dwarf galaxies?” Professor Jerjen asked. “That’s the question we’re working to answer.”

Viesearch - The Human-curated Search Engine

Blogarama - Blog Directory

Web Directory gma

Directory Master

http://tech.ellysdirectory.com

8e3055d3-6131-49a1-9717-82ccecc4bb7a

Viesearch - The Human-curated Search Engine

Blogarama - Blog Directory

Web Directory gma

Directory Master

http://tech.ellysdirectory.com

8e3055d3-6131-49a1-9717-82ccecc4bb7a